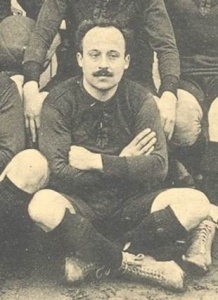

Alfred Mayssonnie in 1912

The odds were always that the first rugby international killed in action in the First World War would be a Frenchman.

The French were the first major rugby nation directly involved, facing a German invasion of their territory almost as soon as the war started.

Stade Toulousain half-back Alfred Mayssonnie – ‘Maysso’ to friends and fans alike – joined up as soon as war was declared, appointed a non-commissioned officer in the 259th Infantry Regiment. Within three weeks he had earned a mention in his regiment’s orders of the day with his bravery in an action at d’Amel-Eton, north-east of Verdun.

ESPNscrum

In little more than a month he was dead, killed on September 6 1914 near the hamlet of Osches in the early stages of the Battle of Marne, one of the key moments in the halting of Germany’s early momentum. His body might, like those of many war victims, have been lost but for his former Toulouse and France team-mate Pierre Mounicq, who buried it while under enemy fire.

Two days later a group of five including Paul Voivenel, a doctor, journalist and rugby administrator and Andre Moulines, a team-mate in the 1912 French championship final, marked the spot with a cross wrapped in the Toulouse colours of red and black. The body now rests in the churchyard in his native village of Lavernose.

Xavier Adrien Albert Mayssonnie was the first of 23 French internationals – more than one fifth of the 112 men who had won caps to that time – killed during the war. His had been a short and eventful international career, encompassing three matches, two of them on New Year’s Day and two away to Wales, the toughest trip of the time.

His debut against England on New Year’s Day 1908 was also France’s first match at the Stade Colombes, their main home until the early 1970s.

It proved an unhappy day both for the hosts, who went down 19-0, and their new scrum-half, who was forced off the field with an injury after only 12 minutes.

He retained his place for the next match, away to Wales in Cardiff, but may not have enjoyed it any more as France went down 36-4.

He was dropped, and recalled only once more, another trip to Wales on New Year’s Day 1910 for the match at Swansea which is now regarded as the beginning of the Five Nations championship.

France found themselves a player short on assembling at the Gare du Nord. They called up Joe Anduran – a good enough player to appear in a French championship final, but whose chief virtue at that moment was that the art gallery he ran was close to the station.

France lost 49-14 and Mayssonnie, by now doubtless extremely sceptical of the concept of a ‘Happy New Year’, did not appear again.

But his greatest moments with his club were still to come. He appears to have been the first Toulouse player picked for France.

The club website lays claim to Augustin Pujol, a member of the first ever French XV, against the All Blacks in 1906. Pujol certainly did play for Toulouse, but 1906 was also the year in which he won a French championship with Stade Francais and both scrum.com’s own John Griffiths and French historian Jean-Pierre Bodis list him as playing for them when he was capped.

The club website also credits Mayssonnie as the strategist of the first great Toulouse teams.

What is evident is that he was a good club man, prepared to switch position – like many a fine French half-back since he was primarily a scrum-half but could also play at outside-half – or drop down levels for the greater good of the team.

National championships were contested at several levels and in 1908, the same year in which he won his first international caps, he was a member of the Toulouse 4th XV which beat Perigueux to win the national title at that level.

There was a 2nd team title in 1909 and further wins with the thirds in 1911 and the fourths in 1913.

In between the last two came the supreme triumph, but even then he was only a member of the Toulouse first XV which took the field at their Ponts Jumeaux Stadium on March 31 1912 for the national championship final against Racing Club because brilliant teenage outside-half Clovis Bioussa was injured.

Mayssonnie was playing outside Philippe Struxiano, the outstanding scrum-half of France’s early years, but Racing – who fielded six French caps to Toulouse’s three – were favourites and led 6-0 at the interval.

Shortly after the break Struxiano put into a scrum on the Racing 22 and, Voivenel recalled, “passed to Mayssonnie who dummied to the right then sliced majestically to his left between Burgun and Lane, fooling them as he went full tilt for the line, evaded the full-back and went over by the posts.”

The conversion followed and momentum shifted permanently Toulouse’s way. An 8-6 win and with it the first of many French national championships was sealed by a try from centre Pierre Jaureguy, whose younger brother Adolphe was to be the star of their champion teams of the 1920s.

The 1908 Toulouse team

Mayssonnie was a veteran of 30 by the time war broke out. At 5’6″ and a little over 11 stone he differed little from many French players of an age when the 6ft1in Mounicq was regarded as a giant. Pictures show a clipped moustache and a suggestion of receding hairline.

Voivenel recalled ‘a slight, unmuscular figure, an honest workman with the air of a teacher or public servant’. An employee in a small family-owned firm, he was a comparative rarity among the lawyers, doctors and other young professionals who proliferated in early French teams.

He was the first of more than 100 rugby internationals to die in the war. The first British international was Scotland’s Ronald Simson, who died eight days later.

The Frenchmen who followed included Burgun and Lane, the Racing Club centres Mayssonnie flummoxed in the 1912 final, and Anduran. There were 80 Toulouse members, including Moulines – killed in a flying accident in 1917 – and a total of 575 players from clubs in the Pyrenees region.

That Mayssonie was not forgotten amid this deluge of blood owes much to Voivenel, who recalled his friend as “The symbol of all that real sportsmen dreamed, wanted and believed”.

From 1922 onwards he campaigned for the creation of a monument to Mayssonnie as a representative of France’s sporting dead.

Voivenel recorded the campaign, along with some brilliantly evocative personal and sporting memories and the considerably less edifying story of his involvement in the suppression of Rugby League under the collaborationist Vichy regime in the early 1940s, in Mon Beau Rugby, one of the French game’s key texts.

The monument took the form of a statue of Hercules the Archer, one of a number by the sculptor Antoine Bourdelle. Unveiled in 1925 by the Mayor of Toulouse, it stands on the banks of the Canal de Brienne, a couple of miles from the Stade Ernest Wallon.

The monument also incorporates a freestanding pillar with an image of Mayssonnie and a more recent stone in memory of Voivenel, who lived until 1975.

A couple of miles further south, the big game visitor to the Stade Municipal need not divert very far to find the Allee Alfred Mayssonnie.

But consciousness is maintained mostly by the tradition that Toulouse’s rugby and other sporting communities gather at Hercules every November 11.

One hundred years after his death, the memory of Alfred Mayssonnie lives on.