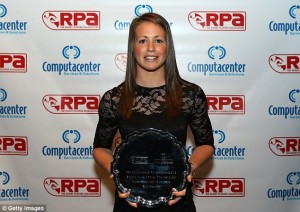

Feminine side: Emily Scarratt receives the England Women’s Player of the Year award in 2013.

The hostility Emily Scarratt suffered for wanting to play rugby as a teenager was made to look even more absurd when she sealed England’s World Cup triumph last Sunday with a superb individual try.

Like the rest of her team-mates, Scarratt is only too aware of the cliches surrounding women’s rugby.

‘Leave it to the men,’ the dinosaurs say. ‘The rugby field is no place for girls’.

dailymail.com

But everyone knows what happened to the dinosaurs and the same seems to be happening to those who argue that the rugby pitch is no place for women. The excellence of Scarratt and her team-mates is helping to change perceptions of a sport that has seen participation levels more than double in the past 10 years.

It is, in business terms, a growth industry.

England’s World Cup winning coach Gary Street says women’s game ‘should go pro’

‘We’re aware of the stereotypes and the view that rugby is a “man’s game” and it’s a view we are working so hard to break down,’ the 24-year-old said at the clubhouse of her former club, Leicester Forest.

‘Those attitudes don’t annoy me because it creates more of a challenge to break them down. It’s a challenge to say, “We’re going to change your mind”. A lot of the people who think women shouldn’t play rugby have never watched it. I would urge them to watch a game. If they are real rugby fans, they’ll appreciate it.’

Best foot forward: Scarratt’s goal kicking was more accurate than Jonny Wilkinson’s

It is hard to argue.

England’s 21-9 victory over Canada, in which Scarratt contributed 16 points, was the last of 30 matches in a compelling three-week competition in France which emphasised the quality and excitement of the sport. Scarratt’s successful goal-kicking percentage of 79 success was much better than Jonny Wilkinson’s in his last World Cup.

An average player weighs about three stones less than a professional male player and that athleticism, linked to an attacking mentality, means there is a view that women’s rugby is better to watch. The dinosaurs roar louder.

Scarratt grew up on her parents’ farm in Leicestershire unaware of stereotypes. ‘I was five when I started playing,’ she said. ‘My brother, Joe, is three years older and my dad took him down to Leicester Forest when he was about eight. I went along with no intention of playing, just for something to do on a Sunday morning.

‘A coach asked if I wanted to have a little pass around. I had a run around and was pretty much hooked from that point on.’

Scarratt, a rangy inside centre who is ‘5ft 11¼in — and don’t round it up’, played alongside boys until she was 12 before switching to a girls’ team. But as a teenager she realised she was breaking the mould — and she was strong enough to ignore the barbs.

‘I did encounter hostility towards me playing,’ she said. ‘I had a very sheltered life growing up on a farm but when I went to college I came across kids who had led much more of a city life who had grown up in a very different way.

‘I don’t want it to sound like a big bullying thing but I definitely encountered hostility. It was just people not understanding why you were able to play rugby or why you would even want to. Especially at that age when it’s more about what you look like, what your boyfriend’s called, how much make-up you’re wearing.

‘I was still interested in all that, but it wasn’t my main focus, which it is for a lot of girls. I loved playing sport, especially rugby.’

With growing interest from TV audiences, which peaked at just over 2 million for a final shown in 137 countries, it appears to be a matter of time before enough investment is available to enable Scarratt and her team-mates to turn fully professional.

The England squad, coached by Gary Street, self-fund much of their season with many of them returning to their ‘proper’ jobs within 48 hours of winning the final in Paris. Scarratt, a PE teacher at King Edward’s School in Birmingham, tells one story of a match last season between her club, Lichfield, and a Bristol side featuring England prop and vet Sophie Hemming, who missed the first 60 minutes after receiving a call-out just before kick-off to deliver a calf.

Does Scarratt worry that by turning professional, women’s rugby could fall into the same trap as the men by placing an emphasis on brawn and power over skill and artistry?

‘You need to be strong for rugby, but the fact we’re women does mean we don’t have the capacity to get so big and personally, I’d never want to get like that,’ she said. ‘I still want to look pretty in a dress! For other girls that’s important, too. I’m still able to do the job I can do looking like I do despite getting grief from the other girls for being puny.’

For now, all Scarratt really wants to do is savour World Cup glory.

‘You waver occasionally and wonder if all the effort is worth it but at moments like this it’s possible to step back and say, “Look what I’ve achieved, look what that hard work and effort have done”.’